Happy days are back, it would seem, for those looking for creative, unusual, thought-provoking cinema that reflects our times, stirs us and disturbs us. The magic of a film is to viscerally relate to it in so many ways, to its intention, story, and most of all, its residual effect in relation to our own daily life and encounters.

Walking tall at Cannes

Very early on, India made its mark at the Cannes Film Festival, walking away with the Grand Prix du Festival International du Film, now known as the Palme d’Or. It was in 1946, Cannes’ inaugural year when Chetan Anand’s Neecha Nagar (on the class differences in our society) won the Grand Prix. In 1954, it went to Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zamin (on a farmer’s struggle to retain his land after being forced to pay back an inflated debt). The same year, V Shantaram's Amar Bhoopali (The Immortal Song) won the award for excellence in sound recording. The film was on early 19th century poet-musician Honaji Bala during the final days of the Maratha confederacy.

From the mid-50s the remarkable Satyajit Ray kept the Indian flag flying high and mighty year after year after Pather Panchali made its mark at Cannes. Thereafter, it was the Berlin International Film Festival that unveiled Ray’s early films to a loyal and admiring audience. Ray along with Ritwik Ghatak, Mrinal Sen and some others struck the clarion call of neo-realism in Indian cinema.

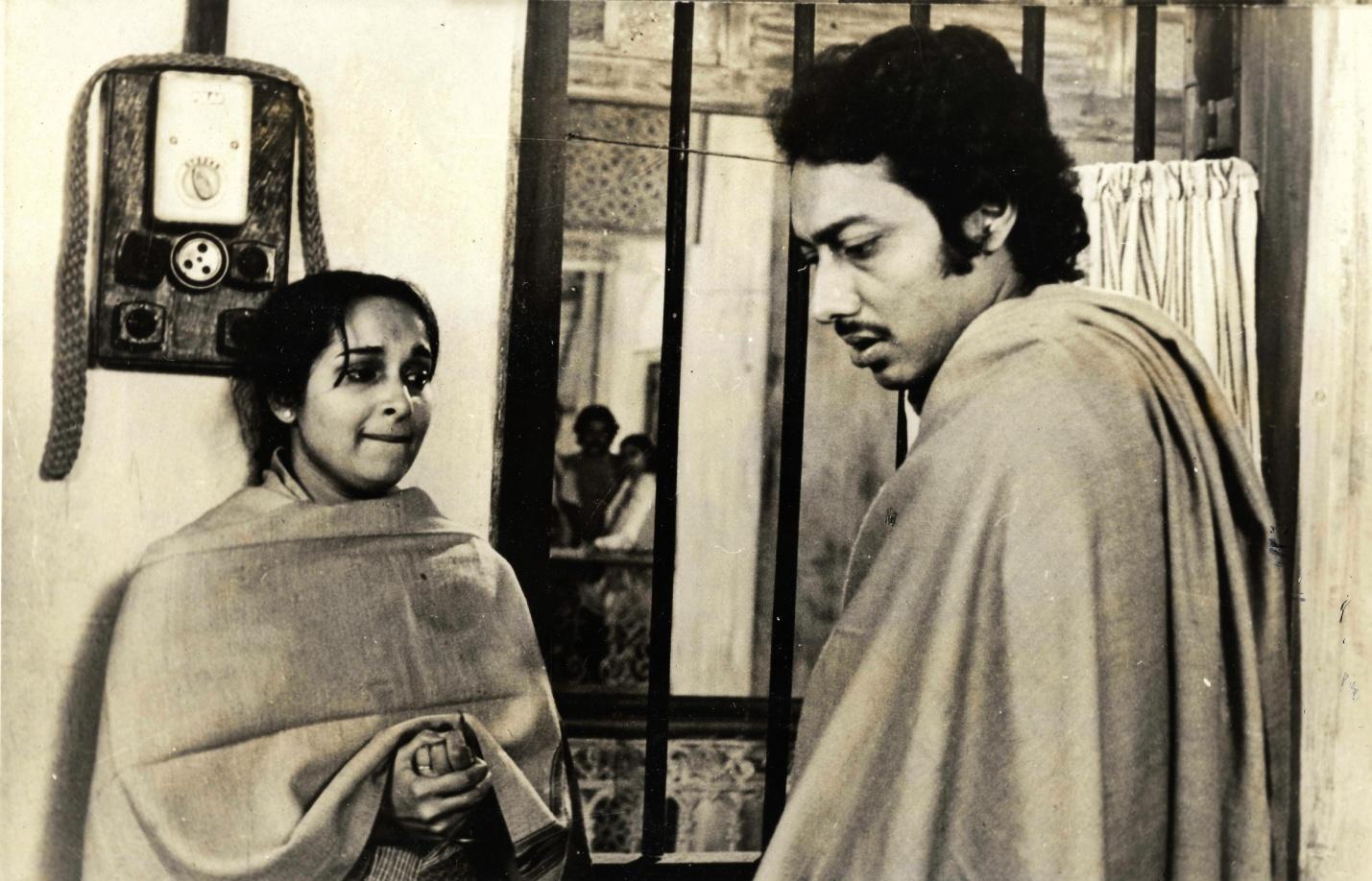

Suhasini Mulay in ‘Bhuvan Shome’

Then the 1970s brought about an outpouring of new talent that practically engulfed the film festival scene. The precursor to this renaissance was Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome, made in 1969. Within a few years, under BK Karanjai’s inspired leadership at the Film Finance Corporation (FFC), the main funder of independent cinema at the time, new Indian cinema flowered and bloomed all across the country, and was eagerly sought after by leading film festivals.

Post-1975, Adoor Gopalakrishnan, Shyam Benegal, G Aravindan, Goutam Ghose, Aribam Syam Sarma and a host of others made their festival mark. I recall the vigilant eye of Ulrich Gregor, who ran the International Forum of Young Cinema, a wing of the Berlin festival, who regularly screened seasons of new Indian films over almost two decades.

It was around the mid-70s that the FFC transformed into the National Film Development Corporation, which became the harbinger of India’s cinematic talent from all corners of the country. This is when Berlin, Cannes, Venice and other festivals that followed went out of their way to have an Indian film in competition, for instance, MS Sathyu’s Garm Hava in 1975.

How did that happen? Working with the Directorate of Film Festivals at that time, I presented a package of path-breaking films by independent directors, which toured five major cities in France. The selectors of the Cannes Film Festival asked if I could withdraw Garm Hava after its Paris screening as they would like it to be in competition in Cannes. I could not believe this, coming out of the blue! The film’s graceful exit led to a fantastic reception at the festival in 1974.

Mamata Shankar and Anjan Dutt in ‘Kharij’

Mamata Shankar and Anjan Dutt in ‘Kharij’

Indian films did well those days. Mrinal Sen won the Competition Jury Prize for Kharij in 1983 at Cannes. Mira Nair’s Salaam Bombay (1988) won the Camera d’Or and the Audience Award. The Camera d’Or (Special Mention) also went Shaji’s Piravi (1989) and Murali Nair’s Marana Simhasanam (1999).

The last Indian film to compete at Cannes was Shaji’s Swaham (1994), which had the advantage of being a French co-production.

Sadly, from the late 80s Indian films only competed in diminishing numbers at these top-rated international festivals. By the mid-90s they were a rarity and finally, after 1999, not visible on the international festival scene. With that, we were no longer the sought-after ones. We had to wage the same battles as others to find an entry into these leading festivals. And featuring in competition at any major European or North American festival has stubbornly eluded us.

A resurgence of creative filmmaking

Abhimanyu Dassani in ‘Mard Ko Dard Nahin Hota’

Abhimanyu Dassani in ‘Mard Ko Dard Nahin Hota’

In the past year and this year especially, there appears to be a glimmer of new creativity and burgeoning talent sparking the Indian film scene. Perhaps inspired by Anurag Kashyap’s fiery example of unbridled energy in film year after year, but creating their own path without aping him, are new names that have gained the eye and respect of film festivals.

In the lead is young Vasan Bala, whose film Mard Ko Dard Nahin Hota which was the first ever Indian film to screen in Toronto’s Midnight Madness section. What’s more, it won the coveted audience award for best film. Then there is Nandita Das’ widely acclaimed, perceptive Manto, which brings alive our recent history and pain of a nation being divided.

The producer-director duo Dheer Momaya and Daria Gai’s Namdev Bhau in Search of Silence is racing through festivals at olympic speed (Busan, BFI London, MAMI, Dharamshala, IFFI-Goa, and more on the cards).

A still from Devashish Makhija’s ‘Bhonsle’

A still from Devashish Makhija’s ‘Bhonsle’

The sombre hard-hitting Devashish Makhija, who brought us the chilling Ajji, with his new film Bhonsle hits deeper but not so intentionally. Here the awe-inspiring actor Manoj Bajpayee excels himself as a former, spent police officer who tragically strikes his last hurrah.

The remarkable Rima Das continues to win laurels abroad and at home. Her latest film, on the teenage pangs of growing up in the confines of rural dictates, Bulbul Can Sing, premiered at Toronto and won MAMI’s top award, while her earlier film Village Rockstars is our Oscar entry this year.

There is the remarkable fantasy-fable tour de force Tumbbad, directed by Rahi Anil Barve and Adesh Prasad, with the mercurial Soham Shah as its producer and lead actor, which opened Venice’s Critics Week. Meanwhile, Ivan Ayr’s female cop drama Soni was in the festival’s Orizzonti Competition. Both are now making the festival rounds.

And last but a leader among them all is Praveen Morchhale, whose latest film Widow of Silence which premiered at Busan is again a festival contender, following his remarkable earlier film Walking with the Wind.

An edited version of this article originally appeared on the online daily newspaper thecitizen.in