51 years since his first film, 41 years since his last, 31 years since he left us ...

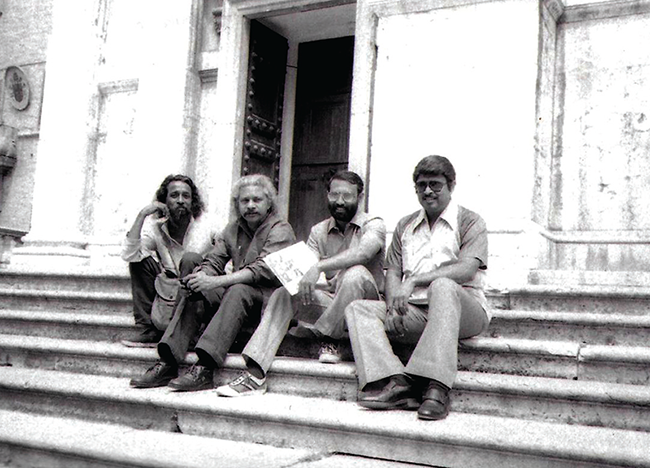

(from left) John Abraham, Adoor Gopalakrishnan, Srinivasan Narayanan and an unidentified delegate at the 1986 Indian Film Retrospective held in Pesaro, Italy / Copyright: Uma da Cunha

Those who knew him took kindly to his startling ways and habits. He was an irrepressible alcoholic and anarchist, but above all, honest to himself and his craft, superbly gifted in a way unique to himself

Anyone fortunate enough to have met and interacted with John Abraham, as I have, will have his unique persona etched in memory for all time. He died unexpectedly, everything he did was unexpected. Approaching the age of 50, he left us, falling off a first-floor balcony. The few films he made shook the contours of cinema, each one challenging and more so, unsettling, both himself and the viewers. Those who knew him took kindly to his startling ways and habits. He was an irrepressible alcoholic and anarchist, but above all, honest to himself and his craft, superbly gifted in a way unique to himself.

We were all part of an Indian delegation, when Srinivasan Narayanan, a name to reckon with in the Directorate of Film Festivals (DFF), coordinated a major Indian Film Retrospective at Italy’s Pesaro International Film Festival with Marco Muller as its programmer. This was in 1986. Adoor Gopalakrishnan (John’s close and caring friend), Shyam and Nira Benegal, Gil Rossellini, Rinki Bhattacharya, Nasreen Munni Kabir, and a host of others were invited, including myself. I recall evenings with John going from restaurant to restaurant, cap in hand, singing Malayalam ditties to gather coins for his next drink. He even played the piano at a café to the amusement of its owner. There was something about John that made strangers chuckle and respond, despite his strange, even off-putting ways.

I recall evenings with John going from restaurant to restaurant, cap in hand, singing Malayalam ditties to gather coins for his next drink. He even played the piano at a café to the amusement of its owner

Narayanan recalls, “In Pesaro, at his own Press Conference, the inebriated John had to be physically placed in his chair. He soon came alive when questions poured in. When asked how he could be both Communist and Christian together, he snapped, 'Don't try to teach me', while pointing out that Christianity came to Kerala much ahead of Italy. By the end of the conference, he was the darling of the local press. John was impromptu, and his repertoire in all fields, including history, literature and music, was rich. So he was both engaging and arrogant, and used his inebriation as an alibi.”

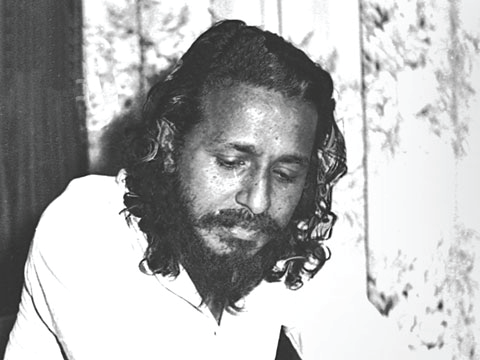

In appearance, John was quaint to the point of being indefinable. He was invariably unkempt, small of build, frail and thin, with a scraggly pointed beard that wiggled with the wind. His probing eyes squinted replies to you that one could not decipher. He was warm, friendly and trusting at all times. But, refuse him a drink, and he would look like a spaniel rebuffed or an angered bulldog (depending on his mood) and leave in a droopy huff that made me, as the host, feel miserable.

In appearance, John was quaint to the point of being indefinable. He was invariably unkempt, small of build, frail and thin, with a scraggly pointed beard that wiggled with the wind. His probing eyes squinted replies to you that one could not decipher. He was warm, friendly and trusting at all times. But, refuse him a drink, and he would look like a spaniel rebuffed or an angered bulldog (depending on his mood) and leave in a droopy huff that made me, as the host, feel miserable.

His foray into films came through his training at Pune’s Film and Television Institute, under Ritwik Ghatak. He began his film career as assistant director on Mani Kaul’s debut feature ‘Uski Roti’ (1969)

Few know his name today. A biopic is being made on this quirky, quintessential filmmaker by journalist-turned-director, Prem Chand. Titled simply 'John', its screenplay/dialogues are being written by his wife, Deedi Damodaran. His daughter Muktha is the producer. Prem Chand says, ‘John’ is not a cradle-to-grave chronicle. Instead, the camera functions as John’s vision, offering a micro-level exploration of his last days via his close friends, co-artistes and family, in and around Kozhikode, Kochi, and Kottayam in Kerala. It has five different cinematographers — Ramachandra Babu, M J Radhakrishnan, Fousia Fathima, Pratap Joseph and Rahul Accot. It took five years to put this project in place. The 75-minute film, shot in 18 days, is scheduled to be ready by year-end.

Born in Chennamkary, Kuttanadu, Kerala, John’s early years were spent with his grandfather in Kottayam. After completing his degree in economics from Mar Thoma College, Tiruvalla, he worked as an insurance agent in Tamil Nadu. His foray into films came through his training at Pune’s Film and Television Institute, under Ritwik Ghatak. He began his film career as assistant director on Mani Kaul’s debut feature ‘Uski Roti’ (His Daily Bread, 1969).

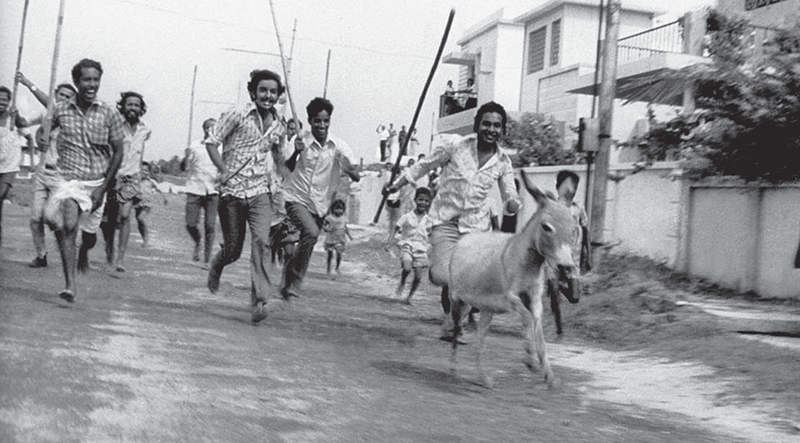

Still from 'Agraharathil Kazhuthai’ (A Donkey in a Brahmin Village)

In his short lifespan, John impacted Malayalam cinema with only four films to his name. His first, ‘Vidyarthikale Ithile Ithile’ (Students, This Way, 1971), was generally disregarded, even by John. In his second film, ‘Agraharathil Kazhuthai’ (A Donkey in a Brahmin Village, 1977), he attacked traditionalists. In Tamil, inspired by Robert Bresson’s ‘Au Hasard Balthazar’ (1966), it is considered his masterpiece. Through the tale of a donkey that strays into a village of orthodox Brahmins, John struck at the roots of religious orthodoxy and they hit back in outrage. Despite the film winning him a National award, Doordarshan was forced to cancel a scheduled TV screening and the Tamil press ignored the film as the Brahmin purists tried to have the film banned.

‘Cheriyachante Kroora Krithyangal’ (Cruelties of Cheriyachan, 1979), John's third film, uses Christian and feudal symbols with Kuttanadu, John’s homeland, as its backdrop.

A retrospective of John’s work — his four films and whatever writing he has left behind and others who have written about him — is long overdue

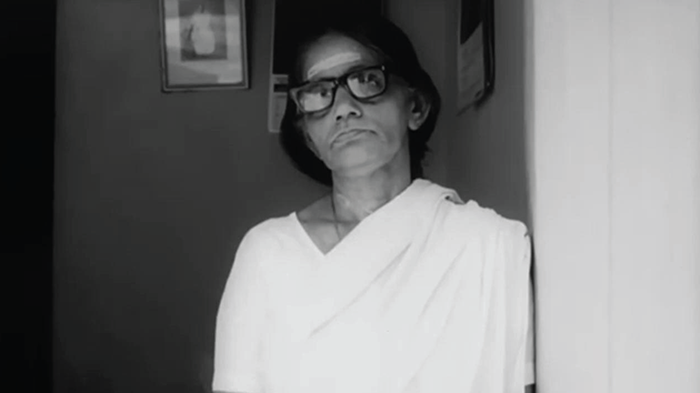

Kunhulakshmi Amma in 'Amma Ariyan’

‘Amma Ariyan’ (To Mother, 1986), his fourth and last film, is the only South Indian film to make it to the British Film Institute’s Top 10 Indian Films of All Time list. Made in a documentary format, it re-defined conventional filmmaking, as it depicted a highly turbulent political era in Kerala.

John’s ideology also had an impact on independent filmmaking. The most key here is the Odessa Collective founded in 1984, which initiated street plays and screenings of popular films (such as Charlie Chaplin’s ‘The Kid’) to raise instant money, kept aside for film production and also to democratise film distribution. John constituted the Collective aiming at the production and exhibition of good cinema with the active participation of the general public, without the intervention of market forces. The Collective raised money, door to door in Kerala’s villages, for one of Abraham’s most critically acclaimed films ‘Amma Ariyan’. This was the earliest, innovative crowd-sourced means of screening films throughout Kerala on a non-commercial basis.

John’s collection of stories was published under the title Nerchakkozhi in 1986 and another published posthumously in 1993, titled John Abrahaminte Kathakal. A retrospective of John’s work — his four films and whatever writing he has left behind and others who have written about him — is long overdue.

Adoor Gopalakrishnan wrote a memoir to the director in his book Cinema, Literature and Life. It has this poignant ending, “Once after a long interval, John visited my home. He asked my daughter: ‘Who asked you to grow up?’ I would like to ask him in return: ‘Dear John, who asked you to die?’”

Courtesy thecitizen.in, published July 8, 2018